ilya + emilia kabakov

paintings about paintings

Holiday #13

Holiday #14

For some reason, these paintings remained in the studio until recently. Again dragged out into the light of day, these works filled the artist with revulsion because all their light and energy have disappeared, the paint has yellowed, they are covered with dust, everything has been transformed into boring murk. And a new impulse emerged for the artist: to renew the series, to return to it once again those qualities that it once possessed, to re-inject those feelings of joy and exultation that were previously present and that were supposed to be there. It is possible that now, after the course of many years, he is compelled to realize these works. One could redo the paintings with rich, bright, emotional colors. But he has neither the strength, nor the time, nor the desire to do so. But the determination to make them cheerful and bright wins out. And he runs to the strangest method for injecting joy—namely, he sews on these flowers.

Time splits in these works. On the one hand, it is old hackwork, made as something remarkable but that by now has lost this remarkableness and is presented here as junk and vileness. And on the other hand, holidays have a place today as well, and demand at any cost that a joyful facial expression be hastily achieved. This is similar to many of our buildings, at one time decorated in intense rose or yellow colors, but over the course of many years they have been covered with dust and soot. However, often before holidays, painters would add another layer of rose and yellow “shininess” without first cleaning the dirt, and this film of shininess renews the past holiday.

The Six Paintings about the Temporary Loss of Eyesight (The Scene at the Square)

The Six Paintings about the Temporary Loss of Eyesight (They are Painting the Boat)

Why do these paintings have such a title, and did the author really develop problems with his vision?

No, there were no problems, and the appearance of gray dots on the whole surface of the paintings has a completely different justification. Any images of “reality” on the canvas don’t make them sufficiently energetically charged (that’s what the author thinks). In real life, such subjects may be interesting and curious, but when presented on the canvas they lose those qualities (if we don’t take into consideration the opposing opinion of the “realist” painters of the nineteenth century).

What kind of solution can be found in this case? We can go back to the experience with the paintings “Holidays” from 1980, where the elements foreign to the painting—paper flowers—are covering its entire surface.

This produces constant vibrational waves on the painted surface, creating in our subconscious an energy pulsation, which, as we mentioned above, will be necessary.

The gray dots in the new paintings substitute the paper flowers, and for an explanation of their strange appearance, we come up with the title, which speaks of a dangerous and sudden eye disease in order to bring into painting a new, dramatic effect.

Charles Rosenthal: The Three Riders, 1927-1928

Charles Rosenthal: The Auction, 1927-1928

C. Rosenthal, fictional personage, obstinately seeks, beginning in 1930, plots which would satisfy his yearning to create a significant work using his beloved Théodore Géricault as an example. At the beginning of 1932, these quests end with the creation of two paintings symbolizing the West and the East. The West for him is associated with the Park Bernett auction that took place in October 1931 in London, which Rosenthal attended as an observer. “I saw art as money…money and nothing more,” he would write later in his diary. Serving as the plot of his “eastern” painting was the gathering of horsemen for a hunt which C. Rosenthal might have witnessed when he visited Calcutta, where he found himself part of a geographical expedition. The spectacle of the three horsemen of the Apocalypse was filled with sorcery and threats.

“The presence of ‘whiteness’ in my early paintings is beginning to oppress me. I want to fill my painting entirely, to the very edges, without any remainders” resounds an entry in his diary around the same year. And yet, the simple realistic painting doesn’t entirely satisfy him. He supplements it with literary texts, placing tables with buttons in front of each of the paintings, uniting the narrative with the visuals, thereby anticipating many of the conceptual quests of the end of the twentieth century. Simultaneously, he introduces into the painting a dimension of time, as well as the appearance of a source of light not only in front of the painting, but also from beyond it, beyond the canvas. This unexpected device serves as the impetus for the creation of his subsequent works.

Three Fragments

Three Fragments

The paintings consist of three parts, which are not connected to each other. The first two parts have images, taken from different periods of time: the fourteenth century and the late twentieth century. In addition, a wooden circle depicting the face of a man is attached to the surface of the canvas. There is some kind of mystery in front of the viewer, a rebus to be solved. We give you one of the solutions.

Two fragments of the image are addressed to our cultural memory, and this memory tells us that we have two worlds, completely different in their artistic and historical significance.

One of them speaks of the sublime and significant. The other is about the banal, insignificant everyday. In any case, both speak of the past, which has little to do with us today and leaves us quite indifferent.

But the whole situation changes because of a little wooden circle with the image of a man. This man, who is looking directly at us, immediately produces an association with a mirror where the viewer is seeing himself. Thanks to this “mirror effect” we can see ourselves, at the present time, standing in front of the painting, but also being integrated into the subject of this painting. Somehow, we become the unwilling participant, a strange traveler in time. And because of this unexpected effect, the two times merge together and “The Three Fragments” is able to hold the viewer’s attention for a long period of time.

In the Museum (Ray from the Window) #1

In the Museum (Ray from the Window) #1

1. Both paintings belong to the type of paintings called “The Curiosities” in the history of art. They have characteristic objects on their surface, which the artist meticulously painted there and which have nothing in common with the general context of those paintings. Why the artist painted them, what they were trying to tell us, remains an enigma for the viewer, demanding a certain effort of their mind. In classical paintings by Dutch, Flemish, and, sometimes, French masters, the same “curiosity” (the fly) appears numerous times, painted much bigger than its natural size. It looks like the artists are competing with each other in their detailed depiction of this insect. Each image also has a shadow projected on the painting.

As far as we know, the reason for the appearance of this insect still remains unknown.

Maybe the artist and his client had a lot of flies in their spaces?

2. But let’s return to our paintings. There is no doubt that the rays of sunlight, because of their brightness and foreignness, prevent us from seeing the paintings and irritate us by their presence. We must try to understand the reasons why they are here. First of all, when we look at the painting, together with the sun beam in the middle of it, we see a stereoscopic effect: the ray of sun somehow gets separated from the surface of the painting and is hanging in the air, making us uncertain if it is even painted there. At the same time, the painting is not a flat image hanging in front of us and acquires an almost three-dimensional quality.

What is all this for? It’s not difficult to guess that we have variations on a baroque subject in front of us. In baroque paintings, the objects which are positioned on the first plane are brightly lit, and all the other objects disappear into the darkness. What is new in our positioning is that because of this curious method, not only separate parts of the painting are disappearing, but the whole painting completely immerses into the dark space, losing the light, lost in the faraway past on the edge of our memory.

The Movement of Darkness #1-3

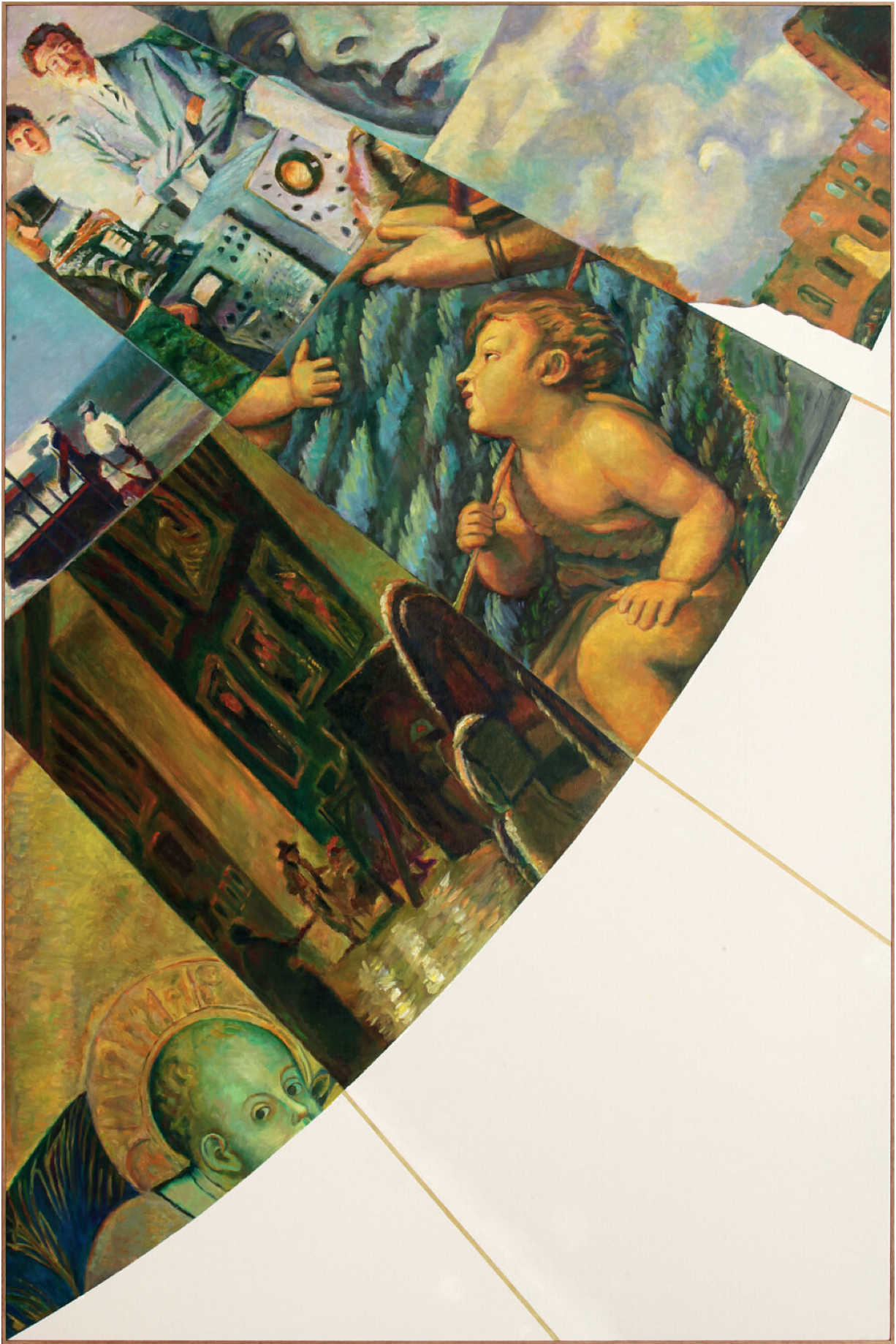

Each painting in this series consists of two separate paintings, which have a strange interaction between them: the left one is encroaching on the right one, and soon, obviously, the right one will not be visible at all. The left one demonstrates its movement with its ripped and sharp edges and because of this, its image becomes even more aggressive and dangerous. The contrast is visible in the images of both paintings: the left is darker, filled with sharp, stabbing lines. In the right one, which is much lighter, there are numerous pure colors, as well as soft, rounded forms. If we view everything collectively, we will see in front of us the intrusion of something gloomy and dark onto the world full of light and calm.

But what constitutes this darkness and light under our careful look? In the darker parts of the paintings we see contemporary, everyday, banal images: at the café, the scientific lab, the chicken farm. In the brighter part, subjects are from the middle of the fifteenth century. But the deep contrast and, at the same time, the main meaning of this contradiction is that the images depict two different periods of history, which themselves produce distinct characters.

At the Studio #3

The subject of this painting refers to the famous masterpieces depicting artists’ studios: “Las Meninas” by D. Velázquez and “The Artist’s Studio” by G. Courbet.

The commonality between “At the Studio” and “Las Meninas” is the presence of two main characters: a small girl and the artist at work. In the Velázquez painting, however, the girl is a stranger both to the studio’s world and to the artist. In “At the Studio,” she is a lawful participant of the studio’s life. She is busy working and the difference in age between the two painters is the work’s main subject; one is at the beginning of her journey, the other at the end of his.

The similarity to “The Artist’s Studio” is no less interesting. They share a depiction of the artist in the background of the painting, which he himself has painted. The painting and the artist in it are painted in realist style. Because of that, the artist is “going” into his painting, becoming part of it. This is the deepest meaning, a precise metaphor: the artist, in the midst of working, transforms into a character of the world he has imagined.

As for the white triangle, which appears in the upper part of the canvas, we will present the explanation when we write “Commentaries for the Paintings, ‘The Movement of White.’”

He Never Came Back

Three subjects are depicted in this painting, each one separate and, at the same time, connected with invisible thin strands. Both painted portions of the canvas belong to different epochs: the one on the right belongs to the baroque, and the one on the left shows the inside of a factory from the middle of the twentieth century. The link between them is the chain of faces, passing through both halves of the painting, like a shared horizon.

But at the same time, this chain also separates them, accenting their differences, such as the shifts of the faces and characters, corresponding to changes in history and time.

The third subject in the work and secured to its surface are a pair of shoes and the green wooden fence, which seemingly have nothing in common with the painting. But the link obviously exists. It is visible in the title of the painting: someone, to whom belongs those shoes, is making two steps, in order to leave forever, to disappear from this world, regardless of his belonging to the long-past world of the baroque or to the recent Soviet one. He doesn’t like either of them. For him, they are surrounded by the fence, which is the reason he always wants to run away.

The Fishermen

It is well known that the modernists’ revolution at the beginning of the twentieth century changed realistic depictions to abstract images such as symbols, geometric structures (Mondrian), and grids (Jackson Pollock). The most important symbols, discovered by Malevich, were the square, the cross, and the circle. The general idea was that the representational world would never come back after the complete victory of symbols over the real.

But after Malevich, we once again returned to the images of reality, and ironically, we placed them at the center of a cross. The same may happen at the center of a square or at the center of a circle. It’s as we say: Never Say Never.

Two Fragments

This painting, like everything else, is turning the viewer's attention to his "cultural" memory, his preliminary knowledge of the history of art, in this particular case to the Russian art of the nineteenth and twentieth century.

But, simultaneously, we are talking about the encounter of realistic and abstract images. Both are positioned in a "floating" position relative to the painting’s vertical and horizontal axes. The tension is created by presenting the fragment of realistic painting in an inclined diagonal position, thereby violating its "normal" orientation of top and bottom. The viewer has a choice: Should they consider what was seen by Repin (and was only a “painting”) to be reality, or is this just empty space in which the scraps of their memories are floating around?

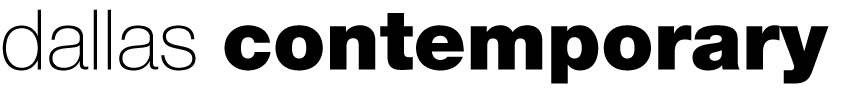

The Half of the Painting #23

The Half of the Painting #24

Buddhists monks have a famous “koan” (a riddle): How do you clap if you only have one hand? In our paintings, only one part is painted and the other is empty. Nothing is there and therefore the painting as a whole simply doesn’t exist. To our minds comes the story about “The Emperor’s New Clothes,” as an example of a bold swindling.

But everything here, like in the story, is not so simple, not so obvious. Entering “the game” are such indirect elements as the geometric construction of the painting itself. The white, or empty part of it, by its space and size mirrors the part which is painted and the laws of symmetry start to work. The big role is played by the form of the painting, the pure square, where both halves are placed diagonal to each other and the thick frame, which unites all optical visions into one whole image.

All those indirect, but active elements, influence the ability for the imagination, hidden in our subconscious, to activate, and we start seeing the painted where it does not exist: “seeing, without seeing.”

It’s exactly the same as how the crowd around the Emperor saw his new suit because the Emperor himself did see it and transferred this vision to his people. Clapping, according to the Buddhist riddle did happen, but it did so only in the imagination of the pupil, through his inner hearing, which “woke” up and started to hear what others couldn’t. The sensible boy in Hans Christian Andersen story was then, after all, not completely right.

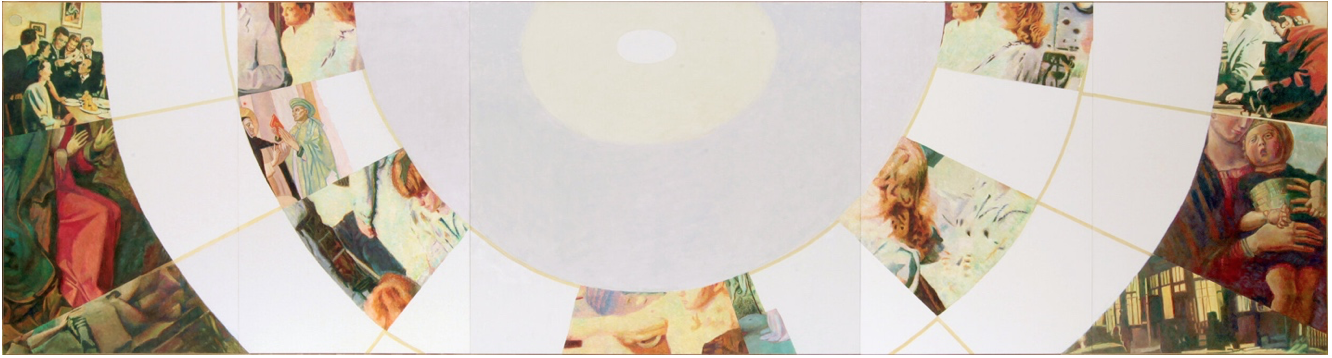

The Movement of White #2

The Movement of White #3

In order to understand both paintings entitled “The Movement of White,” like the painting “At the Studio,” we have to connect them with a certain conceptual point of view, which, albeit in summary, we would like to present here. We are talking about the possibility that our world or whatever we perceive as and name reality, what we see, what we understand, study, and learn from, is only half of reality. The other half cannot be presented in any form. It cannot be understood, nor can our consciousness grasp it, but it does “live” and actively influences our reality and our existence.

But, after all, maybe it can be represented in the form of a “white” image, of “emptiness?” It is the backdrop of everything and sometimes “breaks” through the solid fabric, the surface of our existence.

Returning to our paintings, we can say that on the surface they remind us of old, partially faded tapestry, already ripped in some places. In those places, where the old fabric parts, striking through, shining, is that emptiness, this “white.”

In general, the painting is presenting itself as the artistic image, the metaphor for everything we discussed above.

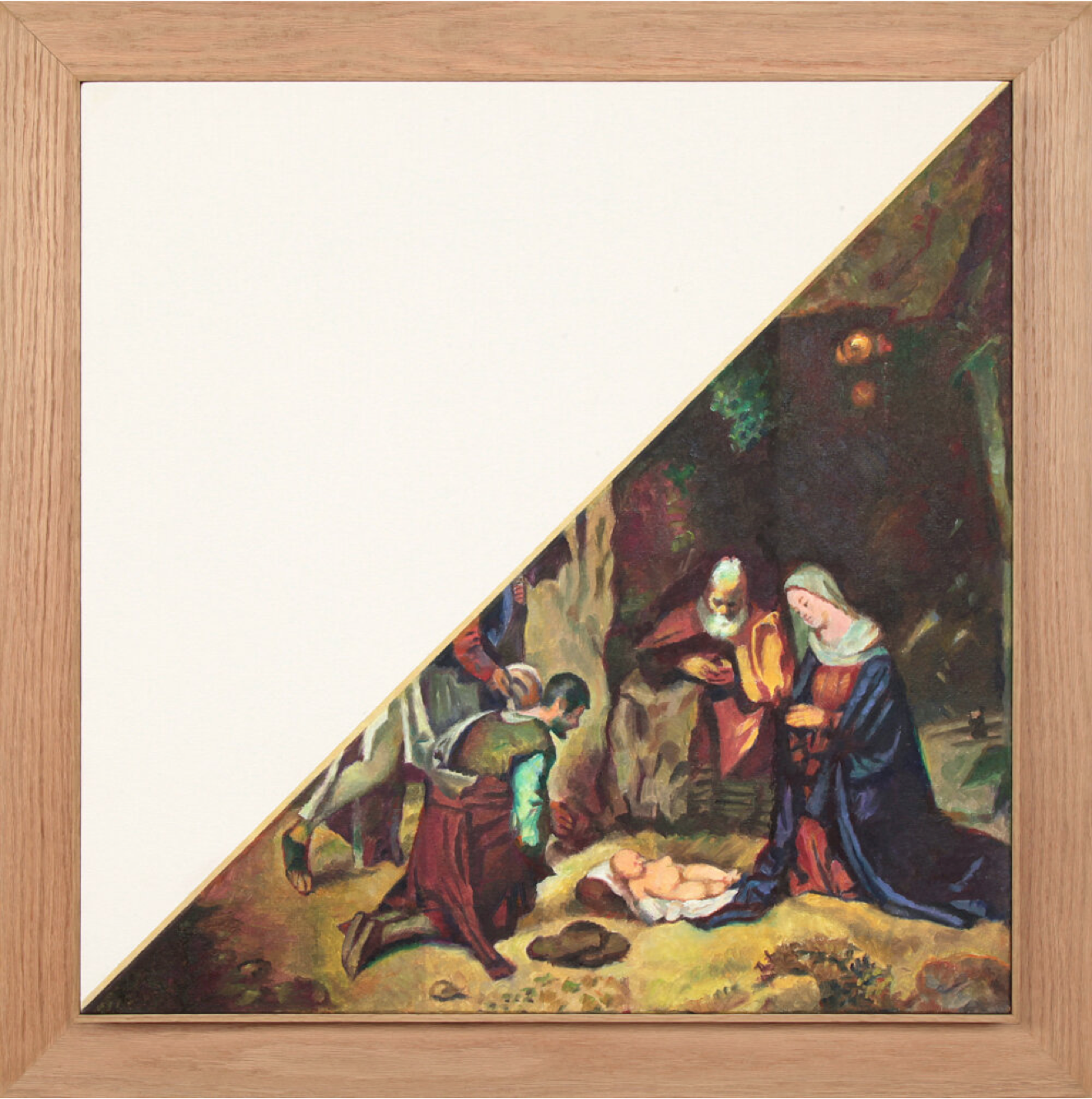

Construction of the Cupola

Addition to the Painting Construction of the Cupola #1

Addition to the Painting Construction of the Cupola #2

Addition to the Painting Construction of the Cupola #3

Addition to the Painting Construction of the Cupola #4

Addition to the Painting Construction of the Cupola #5

Unexpected Solution

In late 2020, I started the painting “Construction of a Cupola.” As in every cupola structure, its construction goes in concentric circles that diminish as they get to the center. At the same time, we can imagine rays going from that center to the foundations of the cupola. The intersections of these rays and concentric circles form a grid and the surface of the cupola will consist of segments that gradually diminish as they approach the center.

So, in pondering my conception I prepared to make these segments one after the other, coming up with subjects for each, assuming that when I had finished them they would fill the entire surface of my cupola (its half) and simultaneously the entire painting.

I drew all the large segments on the edges of the painting and, following my sketches, began moving confidently to its center, filling in several smaller segments. And here I was ambushed by something strange and unexpected.

The point is that the planned painting was rather large (229 x 862 cm) and consisted of five separate canvases which would be put together for the final painting. I made each of the canvases separately, without completing them in full, but just marking in different places the diminishing segments on each canvas.

When I set all of them next to one another against the wall, just to see “how the work was going” and how much more needed to be done to fill in all the segments and thus complete the entire painting, I unexpectedly saw that the painting was “done” and that nothing more needed to be done!

What had happened?

Before executing all the segments, I had drawn thing yellow lines of the grid that I mentioned earlier and in which I had already completed the greater number of segments. So, when I put it all together, the white and the drawn segments formed a strange but convincing unity that led to the unexpected completion of the painting. The white, undrawn segments in that grid next to the “drawn” ones gained from that proximity a special, mysterious meaning that allowed them to take a “legal” place and not simply be unfinished “holes” on the surface; they had become natural participants of the entire artistic whole.

What was that meaning?

In the article “Finished/Unfinished,” I mentioned and examined the hypothesis that next to the “obvious,” real world there is something that we will never see and that in a symbolic, artistic image can be presented as being “white,” empty, incomplete. And now placed next to each other, “depicted” and empty, in the grid system, where they were the same size, their proximity formed that strange completeness, that unity that we can sense only intuitively.

How to Make Yourself Better

How do you make yourself a better, nicer, more agreeable person? This question of how to get rid of your faults and defects has been addressed by more than one generation of moralists, philosophers, and religious thinkers. Some people think it is possible to achieve it by changing the inner “me,” others by respecting moral rules, and still others by refusing earthly temptations. Personally, I have discovered a completely different possibility.

I made two wings out of white fabric and used leather belts to attach the wings to my back. After isolating myself and locking my door, I put on the wings. First, I spend ten minutes attending to my usual occupations. Two hours later, I take the wings off. I then repeat the procedure in the evening.

Very soon, this had positive effects on my character, and I discreetly started mentioning this invention to my friends and relatives. Prudently, I said that I got it from a scientific magazine. This way, it will be safer.

Ilya + Emilia Kabakov: Paintings about Paintings is made possible with lead support from the Timashev Family Foundation and the generous support of Lia Rumma Gallery Milan/Naples, Thaddaeus Ropac (London - Paris - Salzburg - Seoul), Jamie + Robert Soros and PACE Gallery.

about ilya + emilia kabakov

Ilya Kabakov was born in 1933 in the USSR and graduated from the Surikov Art Institute in Moscow. He is considered the main figure of the Moscow Conceptual art movement, prominent in the 1960s through the 1980s, and created the Theory of Total Installation before moving to the West in 1987. Emilia Kabakov was born in 1945 in the USSR and graduated from the Dnepropetrovsk Music Conservatory. She emigrated from the USSR in 1973 and has lived and worked in the USA since 1975.

Ilya and Emilia Kabakov have worked together since 1989. As a duo, they have received numerous honors and awards, including: The Grand Prix Osten Biennial of Drawings, Skopje, Macedonia (2020); The Award for Excellence in Arts, Appraisers Association of America, Inc. New York (2015); Commandeur de L’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres, Paris France (2014); Cartier Prize, St.Moritz, Switzerland (2010). They are Honorary Academics of Vienna Art University, Moscow Art Academy, Sorbonne University (France) and Bern University, (Switzerland). Their artworks are in the collections of MoMA (New York), The Guggenheim Museum, (New York), Tate Modern (London), Center Pompidou (Paris), the Sharjah Museum (UAE), Stedelijk Museum (Amsterdam), and many other museums and private collections.

ilya + emilia kabakov

paintings about paintings

Vacaciones #13 y Vacaciones #14

Por alguna razón, estas pinturas permanecieron en el estudio hasta hace poco tiempo. Nuevamente traídas a la luz del día, llenaron de repulsión al artista porque toda su luz y energía han desaparecido, la pintura se ha amarilleado, están cubiertas de polvo, todo se ha transformado en una aburrida lobreguez. Y surgió un nuevo impulso para el artista: renovar la serie, devolverle una vez más esas cualidades que alguna vez poseyó, reinyectar esos sentimientos de alegría y júbilo que antes estaban presentes y que se suponía que estaban allí. Es posible que ahora, después de muchos años, esté obligado a realizar estas obras. Uno podría rehacer las pinturas con colores intensos, brillantes y emocionales. Pero no tiene ni la fuerza, ni el tiempo, ni las ganas de hacerlo. Empero, la determinación de volverlas alegres y brillantes gana. Y corre hacia el método más extraño para inyectar alegría, o sea, cose estas flores.

El tiempo se divide en estas obras. Por un lado, es un viejo trabajo rutinario, hecho como algo notable pero que a estas alturas ha perdido ese carácter extraordinario y se presenta aquí como chatarra y vileza. Por otro lado, las vacaciones también tienen cabida hoy, y exigen a toda costa que se logre apresuradamente una expresión facial alegre. Esto es similar en muchos de nuestros edificios, en un momento decorados con intensos colores rosa o amarillo pero que, a lo largo de muchos años, se han cubierto de polvo y hollín. Sin embargo, a menudo antes de las vacaciones, los pintores agregaban otra capa de “brillo” rosa y amarillo sin limpiar primero la suciedad, y esta película de brillo renovaba las vacaciones pasadas.

Las Seis Pinturas sobre la Pérdida Temporal de la Vista (La Escena en la Plaza) y Las Seis Pinturas sobre la Pérdida Temporal de la Vista (Están Pintando el Bote)

¿Por qué estas pinturas tienen semejante título? ¿Realmente el artista tuvo problemas de vista?

No, no hubo problemas, y la aparición de puntos grises en toda la superficie de las pinturas tiene una justificación completamente diferente. Ninguna imagen de la “realidad” en el lienzo está cargada de suficiente energía (eso es lo que piensa el artista). En la vida real, estos temas pueden ser interesantes y curiosos, pero cuando se presentan en el lienzo pierden esas cualidades (si no tomamos en consideración la opinión contraria de los pintores “realistas” del siglo XIX).

¿Qué tipo de solución se puede encontrar en este caso? Podemos remontarnos a la experiencia con los cuadros Vacaciones de 1980, donde los elementos ajenos al cuadro, las flores de papel, cubren toda su superficie.

Esto produce ondas vibratorias constantes sobre la superficie pintada, lo que crea en nuestro subconsciente una pulsación de energía que, como mencionamos anteriormente, será necesaria.

Los puntos grises de las nuevas pinturas sustituyen a las flores de papel y, para explicar su extraña apariencia, se nos ocurrió el título, que habla de una peligrosa y repentina enfermedad ocular para dar a la pintura un nuevo efecto dramático.

Charles Rosenthal: Los Tres Jinetes, 1927-1928 y Charles Rosenthal: La Subasta, 1927-1928

C. Rosenthal, un personaje de ficción, busca obstinadamente a partir de 1930 argumentos que satisfagan su anhelo de crear una obra significativa tomando como ejemplo a su amado Théodore Géricault. A principios de 1932, esta búsqueda termina con la creación de dos pinturas que simbolizan Occidente y Oriente. Para él Occidente está asociado con la subasta de Park Bernett que tuvo lugar en octubre de 1931 en Londres, a la que Rosenthal asistió como observador. “Veía el arte como dinero... dinero y nada más”, escribiría más tarde en su diario. La trama de su pintura “oriental” fue la reunión de unos jinetes para una cacería que C. Rosenthal pudo haber presenciado cuando visitó Calcuta, donde formó parte de una expedición geográfica. El espectáculo de los tres jinetes del Apocalipsis estuvo lleno de brujería y amenazas.

“La presencia de ‘blancura’ en mis primeros cuadros está comenzando a oprimirme. Quiero llenar mi pintura por completo, hasta los bordes, que nada quede al descubierto”, resuena una entrada en su diario alrededor del mismo año. Y, sin embargo, la simple pintura realista no le satisface del todo. La complementa con textos literarios, colocando tablas con botones delante de cada una de las pinturas, uniendo la narrativa con lo visual, anticipándose así a muchas de las búsquedas conceptuales de finales del siglo XX. Simultáneamente, introduce en la pintura una dimensión del tiempo, así como la aparición de una fuente de luz no solo frente a la pintura, sino también desde más allá de la obra, más allá del lienzo. Este dispositivo inesperado sirve de impulso para la creación de sus obras posteriores.

Tres Fragmentos

Las pinturas constan de tres partes que no están conectadas entre sí. Las dos primeras partes tienen imágenes tomadas de diferentes períodos: el siglo XIV y finales del siglo XX. Además, un círculo de madera que representa el rostro de un hombre está adherido a la superficie del lienzo. Frente al espectador hay una especie de misterio, un acertijo por resolver. Le damos una de las soluciones.

Dos fragmentos de la imagen están dirigidos a nuestra memoria cultural y este recuerdo nos dice que tenemos dos mundos completamente diferentes en su significado artístico e histórico.

Uno de ellos habla de lo sublime y lo significativo. El otro trata sobre lo cotidiano, banal e insignificante. En cualquier caso, ambos hablan del pasado, que poco tiene que ver con nosotros hoy y nos deja bastante indiferentes.

Pero toda la situación cambia debido a un pequeño círculo de madera con la imagen de un hombre. Este hombre, que nos mira directamente, produce inmediatamente una asociación con un espejo donde el espectador se ve a sí mismo. Gracias a este “efecto espejo” podemos vernos, en la actualidad, de pie frente a la pintura, pero también integrados en el tema de esta pintura. De algún modo, nos convertimos en participantes involuntarios, en un extraño viajero del tiempo. Y debido a este efecto inesperado, los dos tiempos se fusionan y Los Tres fragmentos puede sostener la atención del espectador durante un largo período de tiempo.

En el Museo (Rayo desde la Ventana) #1 y En el Museo (Rayo desde la Ventana) #2

1. Las dos pinturas pertenecen al tipo de pinturas llamadas “Curiosidades” en la historia del arte. Tienen en su superficie objetos característicos, que el artista pintó minuciosamente y que nada tienen en común con el contexto general de esas pinturas. Por qué el artista los pintó, qué intentaba decirnos sigue siendo un enigma para el espectador, lo que exige un cierto esfuerzo de la mente. En las pinturas clásicas de maestros holandeses, flamencos y, a veces, franceses, la misma “curiosidad” (la mosca) aparece en numerosas ocasiones, pintada mucho más grande que su tamaño natural. Aparentemente los artistas compiten entre sí en su descripción detallada de este insecto. Cada imagen también muestra una sombra proyectada sobre la pintura.

Hasta donde sabemos, aún se desconoce el motivo de la aparición de este insecto. ¿Quizás había muchas moscas en los espacios del artista y su cliente?

2. Pero volvamos a nuestras pinturas. No cabe duda de que los rayos del sol, por su brillo y extrañeza, nos impiden ver los cuadros y nos irritan con su presencia. Debemos intentar comprender las razones por las que están aquí. En primer lugar, cuando miramos la pintura, junto con el rayo de sol en el medio, observamos un efecto estereoscópico: el rayo de sol de alguna manera se separa de la superficie de la pintura y cuelga en el aire, haciéndonos dudar de si está pintado allí. Al mismo tiempo, la pintura ya no es una imagen plana que cuelga frente a nosotros y adquiere una calidad casi tridimensional.

¿Cuál es el propósito de todo esto? No es difícil adivinar que tenemos variaciones sobre un tema barroco frente a nosotros. En las pinturas barrocas, los objetos que se colocan en el primer plano se iluminan intensamente y todos los demás objetos desaparecen en la oscuridad. Lo nuevo en nuestro posicionamiento es que, gracias a este curioso método, no solo están desapareciendo partes separadas del cuadro, sino que todo el cuadro se sumerge por completo en el espacio oscuro, perdiendo la luz, extraviado en el pasado lejano al borde de nuestra memoria.

El Movimiento de la Oscuridad #1-3

Cada cuadro de esta serie consta de dos pinturas separadas que presentan una extraña interacción: la de la izquierda está invadiendo la de la derecha, y pronto, obviamente, la de la derecha no será visible en absoluto. La de la izquierda demuestra su movimiento con sus bordes rasgados y afilados y por ello su imagen se vuelve aún más agresiva y peligrosa. El contraste es visible en las imágenes de ambas pinturas: la izquierda es más oscura, llena de líneas nítidas y punzantes. En la de la derecha, mucho más clara, hay numerosos colores puros, así como formas suaves y redondeadas. Si lo vemos todo colectivamente, observaremos frente a nosotros la intrusión de algo lúgubre y oscuro en el mundo lleno de luz y calma.

Pero, ¿qué constituye esta oscuridad y esta luz bajo nuestra atenta mirada? En las partes más oscuras de las pinturas vemos imágenes contemporáneas, cotidianas, banales: en el café, el laboratorio científico, la granja de pollos. En la parte más brillante los temas son de mediados del siglo XV. Pero el contraste profundo y, al mismo tiempo, el significado principal de esta contradicción es que las imágenes representan dos períodos diferentes de la historia, que a su vez producen personajes distintos.

En el Estudio #3

El tema de esta pintura se refiere a las famosas obras maestras que representan los estudios de artistas: Las Meninas de D. Velázquez y El Estudio del Artista de G. Courbet.

El punto en común entre El Estudio del Artista y Las Meninas es la presencia de dos personajes principales: una niña pequeña y el artista trabajando. En el cuadro de Velázquez, sin embargo, la niña es una extraña tanto para el mundo del estudio como para el artista. En Corbe el Estudio del Artista, es una participante legítima de la vida del estudio. Está ocupada trabajando y la diferencia de edad entre los dos pintores es el tema principal de la obra; uno está al comienzo de su viaje, el otro al final del suyo.

La similitud con El Estudio del Artista no es menos interesante. Comparten una representación del artista en el fondo del cuadro que él mismo ha pintado. La pintura y el artista en ella están pintados en estilo realista. Por eso el artista está “entrando” en su pintura, volviéndose parte de ella. Este es el significado más profundo, una metáfora precisa: el artista, en medio del trabajo, se transforma en un personaje del mundo que ha imaginado.

En cuanto al triángulo blanco, que aparece en la parte superior del lienzo, presentaremos la explicación cuando escribamos “Comentarios a las Pinturas, El movimiento del blanco”.

Él Nunca Regresó

En esta pintura se representan tres sujetos separados y, al mismo tiempo, conectado por delgados hilos invisibles. Las dos secciones del lienzo pintadas pertenecen a épocas distintas: la de la derecha pertenece al barroco y la de la izquierda muestra el interior de una fábrica de mediados del siglo XX. El vínculo entre ellas es la cadena de rostros, que atraviesa las dos mitades del cuadro, como un horizonte compartido.

Pero al mismo tiempo, esta cadena también las separa, acentuando sus diferencias, como los cambios de rostros y personajes, correspondientes a cambios en la historia y el tiempo.

El tercer sujeto de la obra y adosado a su superficie es un par de zapatos y la valla de madera verde, que aparentemente no tienen nada en común con la pintura. Pero el vínculo, obviamente, existe. Es visible en el título del cuadro: alguien, a quien esos zapatos pertenecen, está dando dos pasos, para irse para siempre, para desaparecer de este mundo, independientemente de su pertenencia al mundo del pasado lejano del barroco o al reciente soviético. No le gusta ninguno de ellos. Para él, están rodeados por la valla, la razón por la que siempre quiere huir.

Los Pescadores

Es bien sabido que la revolución modernista de principios del siglo XX cambió las representaciones realistas por imágenes abstractas como símbolos, estructuras geométricas (Mondrian) y cuadrículas (Jackson Pollock). Los símbolos más importantes, descubiertos por Malevich, fueron el cuadrado, la cruz y el círculo. La idea general era que el mundo de la representación nunca regresaría después de la completa victoria de los símbolos sobre lo real.

Pero después de Malevich, volvimos una vez más a las imágenes de la realidad e, irónicamente, las colocamos en el centro de una cruz. Lo mismo puede suceder en el centro de un cuadrado o en el de un círculo. Como siempre decimos: Nunca Digas Nunca.

Dos Fragmentos

Esta pintura, como todo lo demás, está dirigiendo la atención del espectador hacia su memoria “cultural”, su conocimiento preliminar de la historia del arte, en este caso particular del arte ruso de los siglos XIX y XX.

Pero, al mismo tiempo, estamos hablando del encuentro de imágenes realistas y abstractas.Ambas se colocan en una posición “flotante” en relación con los ejes vertical y horizontal de la pintura.La tensión se crea al presentar el fragmento de pintura realista en una posición diagonal inclinada, violando así su orientación “normal” de arriba y abajo.El espectador tiene una opción: ¿Debería considerar real lo que Repin vio (solo una “pintura”) o solo se trata de un espacio vacío en el que flotan los fragmentos de sus recuerdos?

La Mitad de la Pintura #23 y La Mitad de la Pintura #24

Los monjes budistas tienen un famoso “koan” (acertijo): ¿Cómo aplaudes si solo tienes una mano? En nuestros cuadros, solo una parte está pintada y la otra está vacía. No hay nada y, por lo tanto, la pintura en su conjunto simplemente no existe. Nos viene a la mente el cuento “El Traje Nuevo del Emperador" como ejemplo de una estafa audaz.

Pero todo aquí, como en el cuento, no es tan simple ni tan obvio. Entran en “el juego” elementos tan indirectos como la construcción geométrica de la propia pintura. La parte blanca o vacía, por su espacio y tamaño, refleja la parte que está pintada y las leyes de la simetría comienzan a funcionar. El gran papel lo juega la forma de la pintura, el cuadrado puro, donde ambas mitades se colocan diagonalmente entre sí, y el marco grueso que reúne todas las visiones ópticas en una imagen completa.

Todos esos elementos indirectos, pero activos, influyen en la capacidad de la imaginación, escondida en nuestro subconsciente, para activarse. Y comenzamos a ver lo pintado donde no existe: “ver, sin ver”.

Es exactamente igual a cómo la multitud alrededor del Emperador vio su nuevo traje porque el propio Emperador lo vio y transfirió esta visión a su pueblo. El acto de aplaudir, de acuerdo con el acertijo budista, sucedió, pero solo en la imaginación del alumno, a través de su oído interno que “despertó” y comenzó a escuchar lo que otros no podían. Después de todo, el niño sensato de la historia de Hans Christian Andersen no tenía toda la razón.

El Movimiento del Blanco #2 y El Movimiento del Blanco #3

Tanto para entender los cuadros titulados El movimiento del Banco como el cuadro En el Estudio tenemos que conectarlos con un cierto punto de vista conceptual que, aunque de forma resumida, quisiéramos presentar aquí. Estamos hablando de la posibilidad de que nuestro mundo o lo que sea que percibamos y nombremos realidad, lo que vemos, lo que entendemos, estudiamos y aprendemos, sea solo la mitad de la realidad. La otra mitad no se puede representar de ninguna forma. No se puede entender ni nuestra conciencia puede captarla, pero “vive” e influye activamente en nuestra realidad y nuestra existencia.

Pero, después de todo, ¿tal vez se pueda representar en forma de una imagen “blanca”, de “vacío”? Es el telón de fondo de todo y, a veces, “se cuela” a través del tejido sólido, la superficie de nuestra existencia.

Volviendo a nuestras pinturas, podemos decir que en la superficie nos recuerdan a un tapiz antiguo, parcialmente descolorido, ya rasgado en algunos lugares. En esos lugares, donde la vieja tela se rasga, trasluciendo, brillando, está ese vacío, ese “blanco”. En general, la pintura se presenta como la imagen artística, la metáfora de todo lo que discutimos más arriba.

Construcción de la Cúpula Adición a la Pintura Construcción de la Cúpula #1-5

Solución Inesperada

A fines de 2020 comencé la pintura “Construcción de la Cúpula”. Como en toda estructura de cúpula, su construcción progresa en círculos concéntricos que disminuyen a medida que llegan al centro. Al mismo tiempo, podemos imaginar rayos que van desde ese centro hasta la base de la cúpula. Las intersecciones de estos rayos y círculos concéntricos forman una cuadrícula y la superficie de la cúpula estará integrada por segmentos que disminuyen gradualmente a medida que se acercan al centro.

Por eso, al reflexionar sobre mi concepción, me dispuse a hacer estos segmentos uno tras otro, planteando temas para cada uno, asumiendo que cuando los hubiera terminado llenarían toda la superficie de mi cúpula (su mitad) y simultáneamente toda la pintura.

Dibujé todos los segmentos grandes en los bordes de la pintura y, siguiendo mis bocetos, comencé a moverme con seguridad hacia su centro, llenando varios segmentos más pequeños. Y aquí me encontré ante la emboscada de algo extraño e inesperado.

El tema es que la pintura planeada era bastante grande (229 x 862 cm) y consistía en cinco lienzos separados que se juntarían para la obra final. Produje cada uno de los lienzos por separado, sin completarlos en su totalidad, solo marcando en diferentes lugares los segmentos decrecientes en cada lienzo.

Cuando los puse todos uno al lado del otro contra la pared, solo para ver “cómo iba el trabajo” y cuánto más se necesitaba para completar todos los segmentos y así completar toda la pintura, vi inesperadamente que ¡la pintura estaba “hecha” y no había que hacer nada más!

¿Qué había pasado?

Antes de ejecutar todos los segmentos, había dibujado unas líneas amarillas de la cuadrícula que mencioné anteriormente y de la que ya había completado la mayor cantidad de segmentos. Entonces, cuando puse todo junto, el blanco y los segmentos dibujados formaron una unidad extraña pero convincente que derivó en la finalización inesperada de la pintura. Los segmentos blancos no dibujados en esa cuadrícula junto a los “dibujados” obtuvieron de esa proximidad un significado especial y misterioso que les permitió ocupar un lugar “legal” y no ser simplemente “agujeros” inacabados en la superficie. Se habían convertido en participantes naturales de todo el conjunto artístico.

¿Cuál era ese significado?

En el artículo “Acabado / Inacabado” mencioné y examiné la hipótesis de que junto al mundo “obvio” hay algo que nunca veremos y que en una imagen simbólica y artística se puede presentar como “blanco”, vacío, incompleto. Y ahora, colocados uno al lado del otro, “representados” y vacíos, en el sistema de cuadrículas, donde eran del mismo tamaño, su proximidad formaba esa extraña completitud, esa unidad que solo podemos sentir intuitivamente.

Cómo Mejorarse a Uno Mismo

Esta cuestión de cómo deshacerse de las fallas y defectos propios ha sido abordada por más de una generación de moralistas, filósofos y pensadores religiosos. Algunas personas piensan que es posible lograrlo cambiando el “yo” interior, otras respetando las reglas morales y otras más rechazando las tentaciones terrenales. Personalmente, he descubierto una posibilidad completamente diferente.

Hice dos alas de tela blanca y usé tiras de cuero para sujetarlas a mi espalda. Después de aislarme y cerrar la puerta con llave, me pongo las alas. Primero, dedico diez minutos a mis ocupaciones habituales. Dos horas después, me quito las alas. Luego repito el procedimiento por la noche.

En poco tiempo, esta práctica tuvo efectos positivos en mi carácter y comencé discretamente a mencionar este invento a mis amigos y familiares. Con prudencia, dije que lo había tomado de una revista científica. Así será más seguro.